As 2018 came to a close, urgency to tackle climate change intensified.

The year was marked by the publication of a landmark scientific report from the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which warned that the world has 12 years to nearly halve greenhouse gas emissions in order to avoid the worst impacts of climate change.

While across the world people are rising up to demand radical climate action, governments have been accused of failing to “deliver what the world needs”.

In the UK, ongoing uncertainty over Brexit leaves many unanswered questions over the future of environmental regulation. Meanwhile, the future of the country’s burgeoning fracking industry appears a bit shaky.

DeSmog UK takes a look at seven environmental and climate stories to look out for in the year ahead.

Brexit

At time of writing, the UK is due to leave the European Union on March 29. Between now and then, anything could happen.

Besides the political circus of the last few weeks, there remains huge uncertainties over environmental safeguards post-Brexit.

The current Withdrawal Agreement and Theresa May’s Brexit deal – the only deal that is currently on the table, remember – includes a non-regression clause that would prevent the country from under-cutting EU environmental standards as they are at the time of the UK leaving in order to create “a level playing field”.

The text of the agreement states that the EU and the UK “shall ensure that the level of environmental protection provided by law, regulations and practices is not reduced” below current EU legislation. This would apply to environmental standards and climate change.

Meanwhile, the non-binding political declaration on the proposed future UK–EU trade deal stressed the need for ongoing cooperation, including on environmental and climate change issues.

While pledges to protect high environmental standards have been largely welcomed by environmentalists, how these standards will be upheld outside the European Court of Justice remains an important question.

There has been wide criticism that the environmental watchdog proposed by environmental minister Michael Gove will “lack the teeth” necessary to hold the government to account and won’t be able to take it to court. Greener UK, an alliance of 13 of the country’s largest environmental organisations, has also expressed concern that the watchdog won’t have any powers relating to climate change.

The Climate Change Act legally compels the UK to reduce its emissions. But in January, the Committee on Climate Change (CCC), the body which advises the government on the issue, warned the UK was not on track to meet its 2025 and 2030 emission cut target. The CCC has no enforcement powers over the UK government, but only reports and advises.

Environmental campaigners have demanded the EU ensures a post-Brexit trade deal with the UK includes an independent environmental watchdog that could take the UK government to court and issue fines for breaking the law on air and water quality, nature protection and waste management.

In the summer, May announced plans for an environmental bill. The bill should be the vehicle to set-out the powers of the environmental watchdog and will determine whether the government is ready to underpin its 25 Year Plan for the Environment with statutory requirements.

A series of proposals for the bill published in December suggest Gove’s watchdog will have the power to sue ministers. But campaigners expressed concern over its impartiality as its budget will be set by the environment secretary. The watchdog’s chairperson will also be chosen by whichever politician occupies the role.

Meanwhile, a parliamentary vote on the Withdrawal Agreement is due to take place in the week beginning January 14. If the agreement is voted down, this could trigger another vote in the form of a second referendum – known as the “People’s Vote” – or even a general election. What happens then is anyone’s guess.

Environmentalists have warned that a “no-deal” Brexit could see a renewed deregulation push from right-leaning libertarian groups.

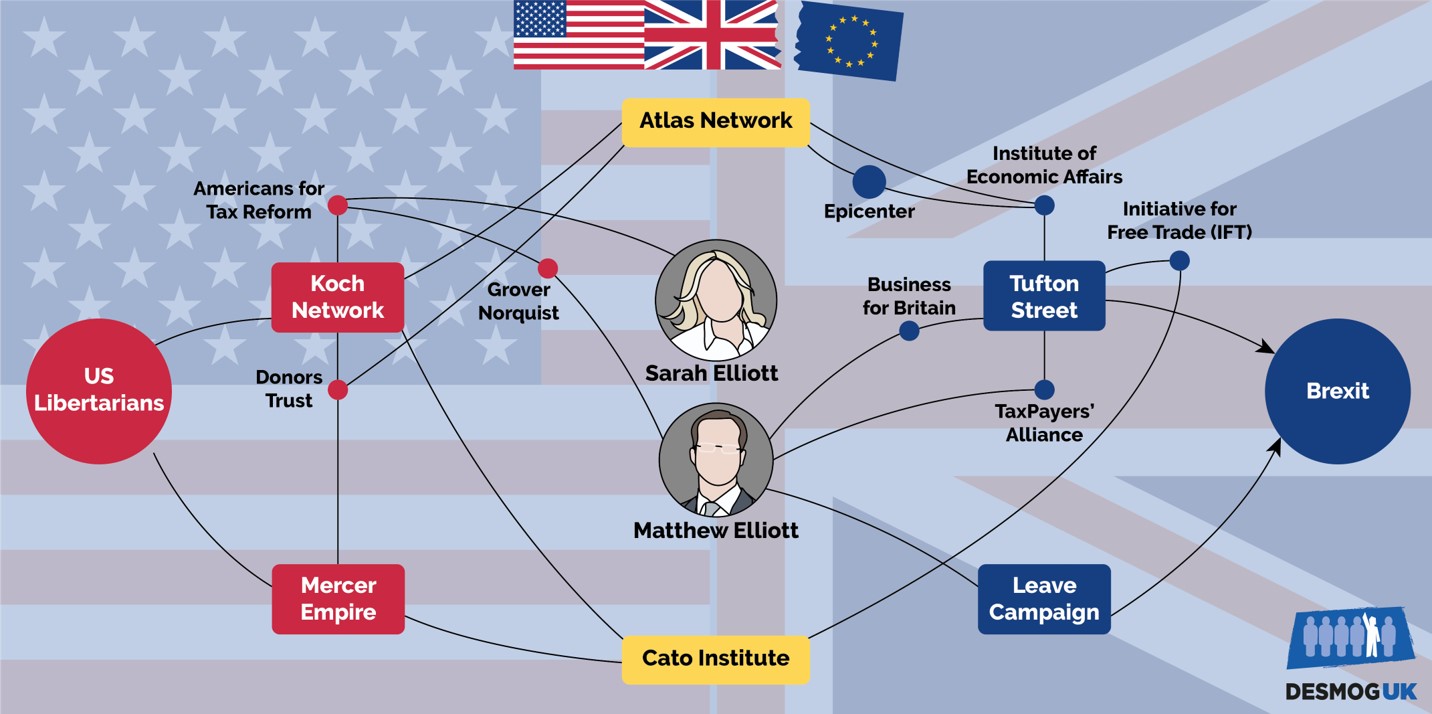

DeSmog UK has extensively reported on the libertarians networks working in and around an office at 55 Tufton Street pushing for deregulation, including of environmental protection and food standards, in order to strike free trade deals with the US.

Our investigations revealed that such groups are connected and have been funded by notorious fossil fuel magnates and climate science denier funders Charles and David Koch.

Even away from Brexit, deregulation still appears to be at the core of government policy.

Earlier this summer the government quietly confirmed further plans to cut regulation that it says will generate savings worth £9bn for businesses by 2022.

The government policy statement listed a series of areas which are protected from the deregulation programme. This includes existing EU regulatory provisions which are due to be incorporated into domestic law, as well as other international obligations. But environmental protection which does not currently fall under EU legislation, such as regulation to protect the natural environment, could yet be cut.

Fracking

Despite strong opposition to the UK government’s fracking policies, energy minister Claire Perry has repeatedly said she would not backtrack on her support for the UK’s burgeoning shale gas industry.

But the future of the industry in the UK appears a bit shaky.

Anti-fracking campaigners have pledged not to give up their protest against fracking after three activists had their prison sentence overturned weeks after they blocked Cuadrilla’s operations at its Preston New Road site late last year.

Image credit: Soapbox.en

Environmental groups have launched fresh legal challenges against the government’s planning rules on fracking. Government proposals include removing the need for exploratory wells to get planning permission in order to fast-track fracking projects through the planning system.

The policy has been widely unpopular with anti-fracking campaigners, who accused the government of trumping local democracy after it overturned a decision by Lancashire County Council to reject fracking plans on planning grounds.

Friends of the Earth is bringing one of the legal challenges to the High Court and hope to force the government to change its planning policy.

Another challenge is brought by campaigner Joe Corré, who argues that latest scientific reports no longer back the suggestion that shale gas could be a “bridge fuel” in the energy transition – an argument that formed the basis of the UK government’s decision to develop the industry.

There has been setbacks on other fronts too.

Fracking company Cuadrilla has been repeatedly forced to suspend its fracking activities near Blackpool because of tremors classified as red under the Oil and Gas Authority’s “traffic light system”, which forces companies to suspend and review their activities if unexpected levels of seismic activities are detected.

Perry previously suggested the level of seismic event triggering a red light on the traffic light system could be increased — comments which have raised serious concerns among campaigners.

Meanwhile, shale gas company Igas, which drilled the first well in the East Midlands, failed to find any gas-rich rocks.

The coming year is likely to test whether government backing is enough to make a success of the repeatedly stalling fracking industry in the UK.

Grassroot movements for radical change

Around the world, people are organising and rising up to demand governments take more ambitious climate action.

Grassroots movements like School Strike 4 Action are hitting headlines. The movement is inspired by 15-year-old Greta Thunberg who refused to go to school and protested in front of the Swedish Parliament until her government took radical climate action.

In the UK, Extinction Rebellion, a non-violent civil disobedience movement, has sent shockwaves through the traditional climate campaigning space and has grown in a matter of weeks into a global call for action.

Image Credit: Thomas Katan for Extinction Rebellion

Meanwhile, the divestment movement continues to make strides with campaign organisation 350.org reporting that more than 1,000 institutions worth almost $8 trillion have committed to divest from the world’s biggest oil, coal and gas companies.

2019 could be another key year for these movement to grow and turn into a global call for action. Campaigners have already pledged to grow international protests to drive climate action after they denounced the lack of progress made at the UN climate talks in Katowice, Poland.

Extinction Rebellion announced an international week of rebellion starting on April 15, hoping to galvanise people around the world.

These people’s movements for the climate have the capacity to grow into some of the biggest mass protests of modern times. How these movements will evolve in 2019 is certainly something to watch.

Renewable energy and technologies

From next year, advantageous tariff payments for households installing solar panels will come to an end.

The government has confirmed plans to end “feed-in” tariff payments for new installations of household solar from 31 March 2019, which means that anyone who installs solar panels from April will not be paid for any excess power they export to the grid.

The change will not affect households who already have solar panels.

The government said it was ending this “export tariff” to minimise costs to all consumers and because the policy no longer aligns with its industrial strategy. It is pushing ahead with the plan despite overwhelming opposition from environmental campaigners.

How the new policy will impact new solar installations on residential buildings is yet to be seen.

Meanwhile, the UK is ramping up investment into technology known as carbon capture and storage (CCS), which captures carbon of power plants and other factories before they are released in the atmosphere.

The technology is widely considered as necessary to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees but has not yet been developed commercially and at scale.

The development of CCS in the UK is expected to see a boost next year with the government hoping to see the first CCS project in the UK to be operational from the mid-2020 and committing £45 million to innovation and construction of the technology.

During the UK climate talks in Katowice, Poland, energy minister Claire Perry announced £175 million of funding to develop new technologies which will help clean carbon-intensive industries such as steel, ceramics, cement, chemicals, paper and glass.

The government has also pledged to begin work early in 2019 to “identify opportunities to transform UK’s fossil fuel infrastructure” and “diversify the oil and gas sector”.

Fossil fuel inquiry

While the UK boasts about its climate leadership abroad, DeSmog UK has repeatedly exposed how a government credit agency was being used to export the UK’s emissions abroad.

However, the House of Commons’ Environmental Audit Committee, chaired by Labour MP Mary Creagh, has launched an inquiry into the UK Export Finance (UKEF) that is tasked with bolstering UK exports opportunities by underwriting loans and guarantees.

The inquiry is due to review UKEF’s activities in the light of the UK‘s climate commitments under the government’s Clean Growth Strategy. Environmental campaigners have accused UKEF‘s activities of directly contradicting the UK‘s commitment to tackling climate change.

A previous analysis of UKEF figures by the Catholic International Development Charity (CAFOD) found that between 2010 and 2014, 99.4 percent of UKEF support for energy went to fossil fuels.

Last year, a joint investigation by Greenpeace’s investigation unit Unearthed and Private Eye found that UKEF had provided fossil fuel companies with £4.8 billion in financial support between 2010 and 2017.

The scope of the inquiry is to investigate “the scale and impact of UKEF’s financing of fossil fuels in low and middle-income countries”.

Written submissions for the inquiry need to be sent by 4 January 2019. The outcome of the inquiry could send a strong signal that if the UK is serious about tackling climate change, it needs to establish consistent policies across government.

This will be one of the environmental moments of 2019 to watch out for.

Big oil on trial

A trial is ongoing in Milan against two of the world’s biggest oil companies in one of the biggest corruption cases facing the industry in years.

Prosecutors are bringing criminal charges against Shell and Eni executives over allegations of corruption regarding a $1.3 billion oil deal in Nigeria — over one of Africa’s most valuable oil blocks.

This is the first time an oil company as large as Shell or senior executives of a major oil company have ever stood trial for bribery offences.

1/ Back at the Milan palace of justice for the Shell/ Eni trial. In the witness box today is Simon Taylor, a founding director of @Global_Witness

Follow for highlights this morning. pic.twitter.com/mxrft11sE7— Barnaby Pace (@pace_nik) October 17, 2018

Analysis from experts commissioned by NGO Global Witness found that the alleged fraud is set to deprive the Nigerian people of an estimated $6 billion in future revenues.

In July, Nigeria became the country with the highest rate of extreme poverty in the world.

In December, two middle-men were convicted of corruption in the case and sentenced to four years in jail. Judge Giusy Barbara told the court that the management of oil companies Eni and Shell “were fully aware” their purchase of the Nigerian oilfield “would have been used to compensate Nigerian public officials who had a role in this matter and who were circling their prey like hungry sharks”.

The case in Milan continues into 2019.

Meanwhile, the Nigerian government has filed a $1.1 billion claim in the UK High Court against Shell and Eni over alleged fraud and corruption. Shell responded that it did not believe “there was a case to answer” in a British court given the proceedings in Milan.

How this second legal challenge will evolve could become clearer during the course of the year.

Separately, the European Union also announced that it will investigate ExxonMobil’s alleged role in spreading disinformation about climate change. The company has been previously investigated in the US over allegations that it knew about the dangers of climate change but deceived the public about its risks.

ExxonMobil has repeatedly rejected the allegations.

On March 21, EU MEPs from the environment, public health and food safety committee are due to questions speakers on misinformation campaigns, which could include representatives from ExxonMobil.

It’s going to be a big year for climate change in the courts.

UN climate talks

Protesters at the UN climate talks in Katowice, Poland. Image credit: Avaaz/Flickr/1.0

Next year’s UN climate talks — or COP25 — will take place in Chile, in South America.

On the road to COP25, an important stop will be the UN 2019 Climate Summit convened by UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres and which will take place in September in New York.

The summit will aim to mobilize political and economic energy at the highest ministerial levels to bolster climate action domestically. Countries, states, regions, cities, companies and investors will be invited to step up action to achieve the energy transition to net-zero carbon societies.

Guterres warned countries at the end of the climate talks in Katowice that in the run-up to the summit his five priorities will be “ambition, ambition, ambition, ambition and ambition” for more action to reduce emissions.

Meanwhile, COP25 in Chile could prove to be an important moment for the UK. British negotiators may have to re-align their position and join a new bloc if, by then, the UK has officially left the EU.

Next year’s talks will also announce the host country for COP26 in 2020 — another key moment for global climate negotiations.

The UK officially launched a bid to host COP26 in 2020, but other countries such as Italy have also expressed an interest. The coming year is likely to see plenty of closed door negotiations to decide who will get to host the next big climate conference.

Image Credit: Jeanne Menjoulet/Flickr/CC BY 2.0

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts