In the summer of 2008, as the price of oil peaked to a record high, a polar explorer and a group of City bankers decided to turn a former gaming company into an oil and gas investment company targeting one of Africa’s most unstable corners: Nigeria.

Investors were told the new business would find an oil asset in the shallow waters of the Niger Delta with the help of a local prince, partner with a company to extract the oil, and sell it on to an oil major for a profit.

To fund this new venture, Sirius Petroleum was listed on the Alternative Investment Market (AIM), London’s junior stock market that allows small companies to raise funds by floating shares. Critics have denounced the market’s weak regulation, which has won the exchange a “casino” reputation.

Behind the scheme was millionaire Andrew Regan and his Cayman Islands-registered investment vehicle Corvus Capital. Together with a group of established City operators, Regan reportedly made a fortune on AIM, buying into shell companies and transforming them into lucrative ventures. Sirius appears to be another example of this strategy.

This third part of DeSmog UK’s Empire Oil investigation shows:

- How the identity of Sirius’ true beneficiaries are hidden through nominee accounts and vehicles based offshore;

- How a tight network of exclusively male and established City lawyers, bankers and accountants financed the new venture — creating complex company structures and connections that fall beyond public scrutiny;

- How the involvement of anonymous vehicles and partners helped Sirius broker deals in Nigeria — a country known for its minimal environmental standards and history of corruption;

- The ties between Sirius and nominee advisors regulating it and their record of advising companies that have been accused of corporate wrongdoing.

A decade after Sirius was formed, not a drop of oil has yet been produced, with shareholders — including high street banks and pensions funds such as HSBC, Barclays and Hargreaves Lansdown — still waiting for the promised returns on their investments. Licensing issues, aborted deals and lengthy funding negotiations were cited by Sirius to explain some of the delays over the development of its oil asset, while thanking shareholders for their “patience”.

Parts one and two of DeSmog UK’s Empire Oil investigation show how extractive companies use London as a hub to pursue polluting activities in emerging markets around the world.

Part one shows how oil companies based in London use the secrecy laws of tax havens which allow companies’ beneficial owners to remain anonymous. The second part highlights criticisms of AIM’s cavalier approach to regulation and weak disciplinary mechanisms, which critics have blamed for creating a safe space for corporate malpractice and wrongdoing.

This final article shows how one company, Sirius Petroleum, used this system of anonymous vehicles and nominee accounts. All individuals and companies named in this story were contacted by DeSmog UK for comment.

DeSmog UK’s investigation does not present evidence of wrongdoing or illegal behaviour by Sirius, but shows how both weak City regulation and the ongoing use of offshore accounts allowed the company to withhold information about its company structure and beneficial owners from investors. Due to this system, and despite operating in Nigeria’s corruption-ridden oil industry, Sirius was able to operate beyond robust scrutiny.

The story falls against a backdrop of calls for regulatory reform on AIM, with critics saying the market’s self-governance is not fit to prevent corporate wrongdoing.

Mark Bentley, director of ShareSoc, a not-for-profit organisation that aims to promote investors’ rights, previously said experienced AIM investors considered the market to be “full of dubious businesses led by dubious people”. He added that the market’s regulatory function “is not fit for purpose” and that “good British businesses, that deserve investment, are tarred in some investors’ eyes with the same brush as the too numerous AIM frauds”.

Following extensive research, important information about how Sirius operates remains hidden from public records, raising questions over the accountability of UK companies run from the heart of London. During AIM’s 23-year history, secrecy over company ownership has repeatedly been at the heart of scandals that have seen companies going bust or kicked off the exchange.

A major investigation by Global Witness previously revealed how former cricketer Phil Edmonds and his business partner Andrew Groves used offshore shell companies to take millions of pounds from investors in a series of questionable Africa-related investments. Edmonds and Groves denied any impropriety.

The publication of the Panama Papers and the Paradise Papers laid bare how tax havens and offshore jurisdictions have been used by the world’s elite and wealthy to launder money, evade tax and finance dirty ventures. At a time when the UK claims to act as a global climate leader, London’s City is still acting as a financing hub for companies carrying out fossil fuel extraction abroad.

The London Stock Exchange, which runs AIM, did not responded to DeSmog UK’s repeated requests for comment.

An extractive company on AIM

London has long been a place where extractive oil, gas and mining companies have met investors to fund their ventures around the world. This is no different for those companies listed on AIM, which boasts a heavy presence of extractive companies — with 190 listed oil, gas and mining companies compared to only 13 operating in “alternative energy”.

While these companies are part of the City’s core financial activities, much information about their ownership remains hidden within opaque offshore accounts.

Most AIM-listed extractive companies are not involved in any wrongdoing or illegal activity, but cases of corruption, fraud and environmental and human rights abuse in countries with weak governance have previously been reported across the sector.

At a time when the world is striving to move away from fossil fuels, calls for transparency and accountability resonate across the industry more than ever before.

The UK is one of 51 countries to have signed up to the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI), a global standard aimed at promoting open and accountable management of a country’s oil, gas and mining resources. Under the scheme, companies incorporated in the UK have to disclose payments made to government agencies, including those that are overseas.

The EITI is to become more stringent, with plans for all countries implementing the scheme to ensure that by 2020 companies that apply for or hold a participating interest in an oil, gas or mining license or contract in their country disclose their beneficial owners.

Who is Andrew Regan?

From its offices in a private business club at the heart of Mayfair and a luxury block in St James’ area, Sirius gives an insight into how small oil companies can flourish on AIM. Sirius’ board of directors includes investment bankers and accountants with many other companies to their names.

One of Sirius’ key backers is Geneva-based businessman and self-proclaimed polar explorer Andrew Regan. A serial lister of small companies on AIM, Regan knowns the ins and outs of London’s junior market. He was credited by Monaco-based entrepreneur Nigel Robertson with establishing the structure for listing cash shells on AIM. Sirius is one example of this.

Regan’s financial dealings have previously come under close scrutiny.

In the late 1990s, Regan was accused by the Serious Fraud Office (SFO) of stealing £2.4 million from his food company and of masterminding a bribery attempt in a bid to take over the Co-op. The Co-op directors involved were later jailed for accepting £1 million.

Following a six-year saga, Regan was eventually cleared of any wrongdoing. In a statement at the time, Regan said: “I have always maintained my innocence and so I am delighted to have been vindicated by the jury’s verdict.”

A decade later, Regan reportedly made a fortune through his offshore investment vehicle Corvus Capital by buying into other cash shell companies and floating them on AIM.

At the time, Regan hailed AIM as “a super place to do business” and praised its regulatory system. “The regulators have done a superb job in creating a good environment: you have got reasonable liquidity and it is a properly regulated area in which to invest,” he said.

Following a record profit of £22.1 million, Regan privatised Corvus Capital in 2008 – which meant information about the company’s backers and owners no longer had to be disclosed.

At the time, Corvus Capital declared it had “moved away from stable cash generating businesses towards more speculative opportunities”. Sirius appeared to be one of them.

FIND OUT MORE ABOUT SHELL COMPANIES HERE

Russian dolls: Secrecy laws and anonymity

Secrecy laws protecting offshore-based entities allow companies to hide the identity of their owners.

It is not illegal for a company to register offshore, neither does it imply its owner is involved in tax avoidance, evasion, or corruption. However, the tax haven system is designed in a way that makes it much more difficult to expose those companies that are involved in such activities.

Sirius’ holding company (a parent company used to own shares of another company) — Sirius Oil and Gas — is registered in the British Virgin Islands. BVI’s disclosure rules mean the owner’s identity is hidden from public records.

In 2008, Sirius entered an agreement with Lagos-registered company Taglient Oil Nigeria Limited, which it described as “a Nigerian private company owned and managed by Nigerian nationals who have considerable knowledge and contacts in the Nigerian oil industry”.

Under the agreement, Taglient agreed to “use all its reasonable efforts to seek out opportunities [for] Sirius”.

According to company records, Sirius Oil and Gas Limited — a subsidiary of Sirius incorporated in England (which is not to be confused with Sirius’ parent company which has the same name and is incorporated in the BVI) — owns 50 percent of Sirius Taglient Petro Limited, a Nigeria-based joint venture between Sirius and Taglient created to carry out business activities in Nigeria.

Records show Sirius Oil and Gas, which is owned entirely by Sirius, has the right to acquire the remaining shares in the joint venture with Taglient and has “management and operating control of the company”. However, Sirius does not disclose the beneficial owner of Taglient Oil Nigeria, whose company records are held in Lagos.

Like a Russian doll, Sirius is set up through a string of nominee accounts and investment vehicles making it difficult to attribute how much of the company is owned by any individual. This is not illegal, but it does make ownership hard to trace.

FIND OUT MORE ABOUT NOMINEE ACCOUNTS HERE

This is how it worked:

Ambeson Limited, a shell company registered in the British Virgin Islands, was used to hold Regan’s shares.

Ambeson Limited was a nominee account for Regan’s investment vehicle Bowden Group Holdings, which was registered in the Cayman Islands, and was later re-registered in the name of Jersey-based Brewin Nominees (Channel Islands) Limited.

Both Ambeson Limited and Brewin Nominees (Channel Islands) Limited were listed among Sirius ’ main shareholders, as they owned more than three percent of the company’s share capital until the end of 2012.

Buying share capital through a nominee account is not illegal. Nominee accounts are commonly used to facilitate share trading and spare investors administrative paperwork. However, senior executives — or anyone with managerial responsibilities — in a listed companies are obliged to notify their companies of any dealings of their shares.

Directors of a company listed on the exchange are also subject to restrictions over when they can buy and sell shares in the company, or could face accusations of insider trading. This means they are dealing shares while having inside knowledge of the company’s activities that has not (yet) been disclosed to shareholders.

Insider trading is illegal and can relate to any employee who has unpublished price-sensitive information about their company when they deal in its shares. There is no evidence that Sirius is involved in insider trading.

Sirius did not respond to DeSmog UK’s repeated requests for comment.

Daniel Balint-Kurti, head of investigations at NGO Global Witness, who has worked with the team credited with revealing some of AIM’s biggest scandals, described DeSmog UK’s investigation as “fitting into the bigger picture”.

He described AIM as “a closed shop” and “a boys’ club with no serious scrutiny, where companies run a serious risk of malpractice”. He added:

“The fundamental issue remains that there is no proper enforcement and self-governance does not work.”

The use of offshore accounts that protect the company owner’s identity have been highlighted as a key element of fraud allegations against AIM-listed companies.

In 2015, one of AIM’s most highly traded companies, mobile technology company Globo Plc, was forced off the stock exchange after it was revealed the company stood accused of the “falsification of data and the misrepresentation of the company’s financial situation”.

A report by equity fund Quintessential Capital Management claimed that Globo had created “fictitious sales” from shell companies located offshore which were posing as legitimate clients, while other shell companies were posing as fake suppliers. It also accused the company of having “fabricated financial statements”.

The Financial Conduct Authority opened an investigation into the allegations. Globo’s chief executive resigned after admitting “falsification of data” and having “misrepresented the company’s financial situation”.

Controversial Romanian businessman Frank Timis also used his AIM-listed mining company African Minerals to personally authorise a $50 million (£37 million) payment to a shell company in Cyprus in which he owned a secret stake, an internal investigation by the company revealed.

The report stated that Timis “strongly denied the allegations” and that an independent investigation “did not discover any direct evidence to support the allegations which were therefore neither proved nor disproved”.

The following year, African Minerals, once AIM’s most highly valued company, went into administration.

A Nigerian affair

Global watchdog Transparency International has identified Nigeria as one of the most corrupt countries in the world, with low environmental and human rights standards. Oil majors Shell and Eni are currently standing trial for bribery over the purchase of an offshore oil field in Nigeria in one of the biggest cases to hit the industry in recent years.

A child fishes in an oil-polluted river in Ogoniland, Niger Delta, several spills by oil giant Shell a decade ago. Image credit: Milieudefensie/Flickr/CC BY–NC–SA 2.0

Through its connections in the Niger Delta oil industry, ties to government officials and a crafted PR strategy, Sirius presented its Nigerian venture as a lucrative opportunity for its shareholders.

The company said it was “confident” of its capacity to exploit a marginal oil field, citing its network of contacts in Nigeria including within “the Lagos state government, the Central Bank of Nigeria, the Nigerian tax authorities, NNPC [Nigeria’s state run oil company] and other major oil companies”. There is no suggestion that Sirius was involved in illegal activity in Nigeria.

Chris Newsom, from Stakeholder Democracy Network (SDN), an NGO which works to empower communities in the Niger Delta affected by oil drilling, told DeSmog UK about the risks associated with exploiting marginal oil fields in Nigeria.

“The shallow waters of the Niger Delta are vulnerable to so many things,” he said, citing the return of militant groups as “not off the cards”.

“Thinking that offshore oil exploitation is more secure is just not true, especially for a company new to the oil sector in Nigeria,” he added.

FIND OUT MORE OIL EXPLORATION IN THE NIGER DELTA HERE

Nigerian connections: A university graduate and a local prince

Olukayode Olufemi Kuti was 23-years-old when he was appointed to the board of Sirius to act as “the interface between the company and its Nigerian operations”. Sirius described him as being “instrumental in successfully establishing the company’s business network in Nigeria”.

According to the company, Kuti studied economics and psychology at Duke University, US, and worked as an “investment advisor for a South African investment fund, Huxton Capital”.

The South African company registrar shows Huxton Capital is located in Plumstead, London, while Kuti’s address on Companies House refers to an apartment block in Bayswater, London. How this London-based university graduate with no reported experience in the oil and gas industry secured a position at the top of an AIM-listed company remains unclear.

In 2013, Kuti was appointed chief executive of Sirius and remains at the head of the company today. He was not the only person appointed by Sirius for his strategic connections in Nigeria.

Babatunde Olusegun Agboola, a former ExxonMobil employee, joined the company as its non-executive chairman after 30 years in the oil and gas industry in Nigeria. Agboola was also connected to two Nigerian-based companies, Bolad Energy and RT5 Petroleum Limited, founded by former ExxonMobil and Chevron employees.

Both companies entered an agreement with Sirius to use “their local knowledge, contacts and significant experience in the region and industry” to provide Sirius with “exclusive” opportunities, the company said.

RT5 Petroleum was responsible for “managing all aspects of the interface with the Nigerian government and local communities”. RT5’s chairman Prince Tunde Akindele, was described by Sirius as well-connected in the Ondo state of the Niger Delta where Sirius’s oil asset is located.

“A native of Okitipupa, in Ondo State”, the prince was described by Sirius as having “considerable local knowledge and contacts”. Akindele was on the board of directors of the African Business Roundtable, an association of business leaders set up by the African Development Bank, and was an executive member of the association of Petroleum Products Importers and Traders in Nigeria.

On the lookout for marginal oil fields in the Niger Delta

Extractive companies seeking assets in developing countries with known corruption or a lack of information about geological resources are “a particular risk” for fraud, Daniel Balint-Kurti, of Global Witness, previously told DeSmog UK. He pointed to prior cases of companies overstating the value of their asset to attract investors.

AIM investors can be dependent on company news to stay informed about various venture’s progress, particularly when a company’s assets are located abroad.

This can sometimes lead to disclosure problems.

In 2009, Regal Petroleum was fined a record £600,000 by AIM’s disciplinary committee for failing to ensure the information notified “was not misleading, false or deceptive”. The company had been accused of issuing a series of misleading statements telling investors it had found an oil field worth $1 billion (£74 million) which turned out to be commercially unviable.

In a statement, Regal Petroleum said it was “disappointed at the outcome” and added “there was no suggestion that its management team “conducted their responsibilities in anything other than a proper and professional manner.”

While not legally required to do so, Sirius appears not to have shared all of the information about its assets with shareholders, DeSmog UK has found.

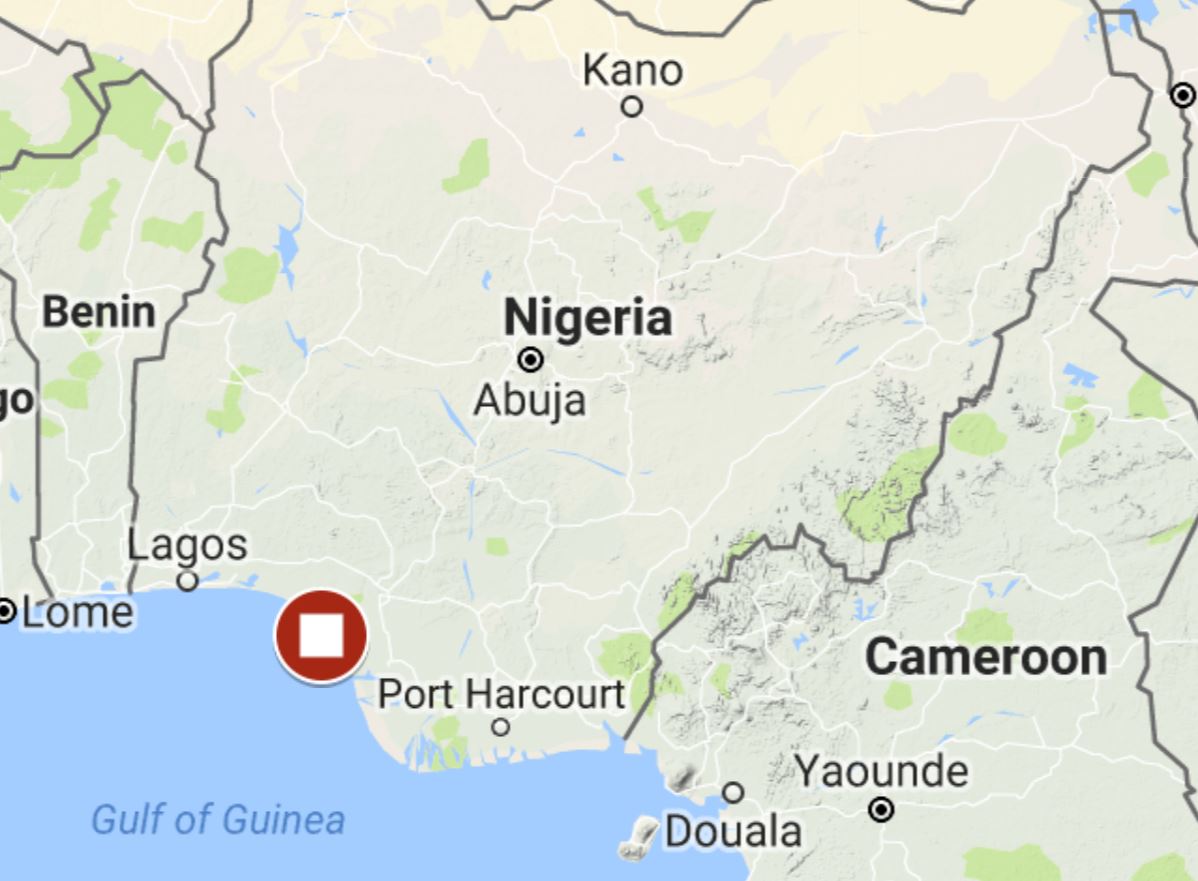

In October 2011, Sirius entered a strategic partnership with Owena Oil and Gas — a vehicle owned by the Ondo State in Nigeria — and Guarantee Petroleum over the development of the Ororo marginal oil field (OML95 block).

The location of the Ororo oil field (OML 95). Image Credit: Google My Maps

Owena Oil and Gas has reportedly been involved in litigation with the Ondo State after a lawyer and four others were accused of forgery and irregular dealing with the records of the company and of alloting shares to some individuals.

One local specialist outlet reported that a government official unlawfully received half a million dollars from Sirius over the sale of Owena’ share in the Ororo field, without the approval of its board of directors.

The Federal High Court in Lagos reportedly fixed a hearing for 9 October 2014 for the “consolidation of the suit” filed by Owena Oil and Gas against the Ondo State Government over alleged conversion of its assets. DeSmog UK could find no reports on the outcome of the hearing.

‘Boys’ Club’

A close-knit network of advisors have been involved in overseeing Sirius’ activities during its time on AIM.

The market’s regulatory system encourages close ties between listed companies and the private companies they pay to regulate them, also called nomads. Over the years, critics have blamed this structure for failing to prevent previous cases of malpractice.

Part two of DeSmog UK’s Empire Oil investigation outlined this system in detail.

In the last 10 years, four different companies have acted as Sirius Petroleum’s nomad and were responsible for carrying out due diligence on the company throughout its AIM listing. These were Canaccord Adams, Strand Hanson, Cairn Financial Adviser and Cantor Fitzgerald.

Strand Hanson declined to comment but a spokesman said the company “abides by all relevant law and regulation at all times”. No other nomad responded to DeSmog UK’s request for comment.

Each of the companies have strong ties with Sirius’ board of directors, sometimes acting as its broker, or have a history of advising companies that delisted from AIM amid allegations of corporate wrongdoing and fraud.

Two of Canaccord Adams’ senior employees joined Sirius’ board of directors when Canaccord was acting as the company’s nomad.

Cantor Fitzgerald, Sirius Petroleum’s current nomad, also has a history of advising companies who went on to be involved in alleged corruption cases. In 2016, Cantor Fitzgerald resigned from advising AIM-listed Sable Mining after its chief executive Andrew Groves was indicted for corruption and bribery in Liberia, Reuters reported.

In February, Groves issued a statement claiming all charges against him and Sable Mining were “irrevocably dropped by the Liberian authorities”. It added: “Both Mr Groves and Sable Mining strongly refuted any allegation that they had acted unlawfully in relation to Sable’s business affairs in Liberia or indeed elsewhere.”

Speaking to Global Witness, Fonati Koffa, the man who oversaw the Liberian task force charged with investigating allegations of bribery against Sable Mining and Groves claimed he was aware of no “comprehensive investigation” that “exonerated these people”, adding: “As former chairman of the task force I would have been notified.”

Cantor Fitzgerald bought Seymour Pierce, a private company that acted as the nomad for mining firm Camec, itself accused of dubious activities in Zimbabwe and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

In 2011, Seymour Pierce received a record fine by the London Stock Exchange for breaching AIM rules and failing to “undertake due diligence and to properly assess the appropriateness of a company seeking admission to AIM”. Seymour Pierce was the largest nomad on AIM, advising 74 companies. Its senior team continued to work for Cantor Fitzgerald.

Seymour Pierce’s chief executive Phillip Wale at the time said in a statement that he agreed with the findings and accepted the sanctions. “Since these events, we have put in place major changes and are confident that our systems and procedures are now of the highest standard,” he said.

FIND OUT MORE ABOUT SIRIUS PETROLEUM’S NOMADS HERE

On at least one occasion, work to establish the veracity of Sirius’ oil asset appears to have gone uncompleted.

In 2011, Professor Chris Toumazou, a chief scientist at the Institute of Biomedical Engineering at Imperial College in London, was contracted to use his contacts in the petroleum industry to estimate the oil reserves of the Ororo fields.

Professor Toumazou was no stranger to Regan. Indeed the pair worked together during Regan’s first transantarctic expedition in 2010 — Regan’s main claim to being a polar explorer.

But it appears the estimation of oil reserves by Professor Toumazou’s contacts never happened.

In an email to DeSmog UK, Professor Toumazou confirmed he had agreed to provide “consultancy services” to Sirius Petroleum but “was never called upon to do so”. He added he “believed that Sirius has never in fact produced any oil or gas”.

The company also announced it may have an opportunity in two further oil blocks referred to only as “the First and Second Oil Block”.

Retired professor and co-founder of the Centre for Quantitative Finance at Imperial College London Nicos Christofides, whose research was previously funded by BP, and his firm sw7reseαrch, were named to estimate the reserves of “the First Oil Block” reported to hold in excess of a billion barrels of oil.

Christofides received a £150,000 payment by Sirius but the barrels never materialised.

DeSmog UK did not find any examples of similar work carried out by Christofides, who did not respond to requests for comment.

In a PR blunder, the company forgot to include any experience Christofides had in evaluating oil reserves when announcing the news to its shareholders. Instead, a note in brackets stating “[include here any relevant experience in valuing oil and gas assets, and for which companies]”.

Screenshots from Sirius Petroleum company news.

There is no suggestion that Christofides behaved improperly in producing any oil reserve estimates for Sirius.

Michelle Madsen, a freelance investigative journalist who has done extensive work on AIM, told DeSmog UK that a “conflict of interest culture” is proliferating “among advisory services in the City, including among lawyers and PR firms which have a vested interested in these companies doing well”.

Stressing the role of PR firms working for AIM-listed companies, she said: “The UK sells itself as a financial hub with policies directed to maintain London as a financial centre. But this financial hub is also built on lies, fraud and enforces no regulation to sort these things out.”

There is no suggestion that Sirius used company news to mislead investors nor that the London Stock Exchange is directly supporting corporate wrongdoing.

However, Madsen’s comments point out to the tightly knit network of companies which provide the City with financial services and work with AIM-listed companies.

In the summer of 2017, Sirius announced an off-take agreement with BP, which would see the oil major buy any oil produced by Sirius’ asset. A spokeswoman for BP confirmed the deal with Sirius which told shareholders oil drilling would start in April this year. At the time of writing, no oil has yet been produced.

The deal with BP illustrates how a small company such as Sirius can carry out on the ground work in potentially risky contexts while allowing larger companies to market the oil and profit too.

What Now? The Vancouver Example

Markets with similar regulatory structures to AIM have run into difficulties in the past.

Before its closure, the Vancouver Stock Exchange attracted a host of small companies focused on oil, gas and mining exploration. In 1989, the Vancouver exchange was described as the “scam capital of the world” in a Forbes magazine article.

In 1999, the exchange merged into the Canadian Venture Exchange after a report by commissioner James Matkin, seen by DeSmog UK, said it was riddled with malpractice, blaming the market’s regulation system.

Matkin’s report found that although some small companies had been successful on the exchange “these successes were overshadowed by the continuing occurrence of shams, swindles and market manipulations”.

Matkin blamed “inappropriate, partisan appointments” for eroding the business community and denounced the exchange’s “passive” regulators for failing to address “recurring problems such as market manipulation, poor quality of listings, conflicts of interest, insider trading and misuse of proceeds”.

He added the Vancouver exchange should “improve its efforts to provide investors with easy access to timely information”, arguing this would allow investors “to better protect themselves from bad players and scams”.

The report called for a “significant restructuring of the system of securities regulation” and stated the exchange’s “self-regulatory responsibility for administering broker discipline must change”, calling instead for the establishment of an independent regulatory agency.

A New York Times article reporting on Matkin’s findings described the Vancouver Stock Exchange as a place where “flim-flam is common and protections are few, where information is scarce and risks are high”.

The story added “fraudulent dealings on the Vancouver Stock Exchange stretch from the history books to the latest headlines”.

Campaigners have warned the London Stock Exchange of similar practices happening on AIM. And calls for reforms are intensifying.

Investigative journalist Madsen called for a complete change of AIM’s regulatory framework and warned the existing system was threatening the whole foundations of London as a trusted financial centre.

“AIM does have some rules and regulations but rarely does anything to enforce them,” she said, adding:

“To have a market which is functional for both companies and investors, you need to have a level playing field which means having the same rules for all companies and a regulator that can act properly because it has the funding to do so.”

In a speech about the future of the economic partnership with the European Union, UK prime minister Theresa May used the reputation and influence of the City to call for a “unique and unprecedented partnership” with the EU.

She said London was “the world’s most significant financial centre” and that the government will be setting out “how financial services can and should be part of a deep and comprehensive partnership”.

With the UK government keen to retain London’s financial influence in a post-Brexit world and AIM now worth more than £100 billion, the issue of the exchange’s regulation is back on the agenda.

Read Part One — ‘Black Gold’: Mapping London’s African Oil Hub

Read Part Two — Taking AIM: London’s Wild West Stock Market

Got a tip or story? Here’s how to contact us securely.

Editors: Mat Hope, Mike Small, Kyla Mandel, & Christine Ottery; Graphics: Sam Whitham; Other multimedia: Jill Russo

Main image credit: Friends of the Earth Internationa/Flickr/ CC BY–SA 2.0

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts